Source: Wisconsin Watch

Wisconsin judge under investigation for jailing man over dispute with courthouse employee

Judge Mark McGinnis has come under investigation after he jailed a man over a contract dispute with a courthouse employee.

Click here to read highlights from the story

- Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis is under investigation after jailing a cement contractor who appeared before him for an unrelated felony probation hearing in 2021.

- The contractor was working for a woman who also works at the Outagamie County courthouse.

- Legal experts question the basis for McGinnis’ action and note criminal hearings cannot be used to settle civil disputes, especially when a judge knows one of the parties involved. However, judges are rarely punished for actions they take from the bench.

Hortonville contractor Tyler Barth was more than halfway through his 18 months on felony probation for attempting to elude an officer when the judge ordered him into court.

Recently he had been caught driving to work on a suspended license. And THC was found in his system during a drug test; he told his probation officer he used marijuana to treat his back pain.

“But it’s not an excuse,” he told the judge who presided over his conviction for attempting to elude an officer during a 70 mph vehicle chase.

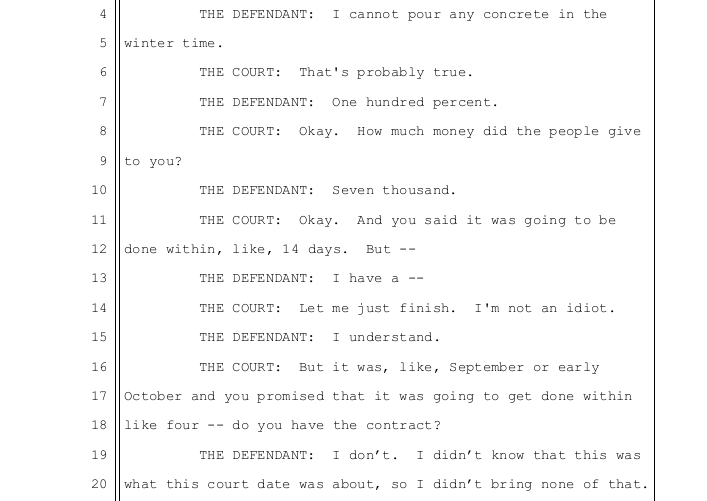

But the weed and traffic ticket weren’t the only thing Outagamie Circuit Court Judge Mark McGinnis wanted to talk about. He told Barth there were “several thousands of dollars that you took from somebody,” according to the Dec. 20, 2021, court hearing transcript.

Barth protested that he hadn’t stolen any money. The judge looked at the clock.

“It’s, like, 11:02, so that’s going to be paid back by 11:15 today,” McGinnis said. “Or do you need more than 13 minutes?”

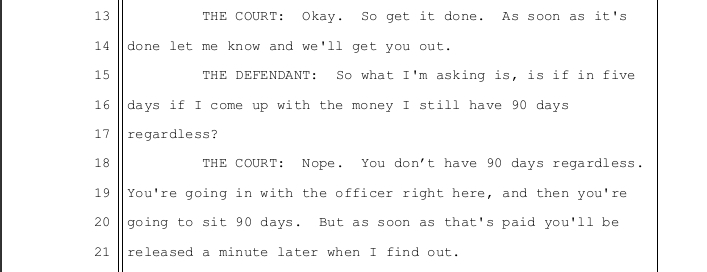

Barth asked for a week, then 24 hours to collect the money. McGinnis denied the request and told him he would spend up to 90 days in jail.

“As soon as that’s paid you’ll be released a minute later when I find out,” McGinnis said before he adjourned. Barth was led away by sheriff’s deputies expecting to spend Christmas and New Year’s behind bars.

What few people in the courtroom knew at the time was that Barth had received an ominous warning from a business client who was upset he was holding a $7,000 deposit for a concrete pouring job in Oneida County that had been delayed due to the cold weather.

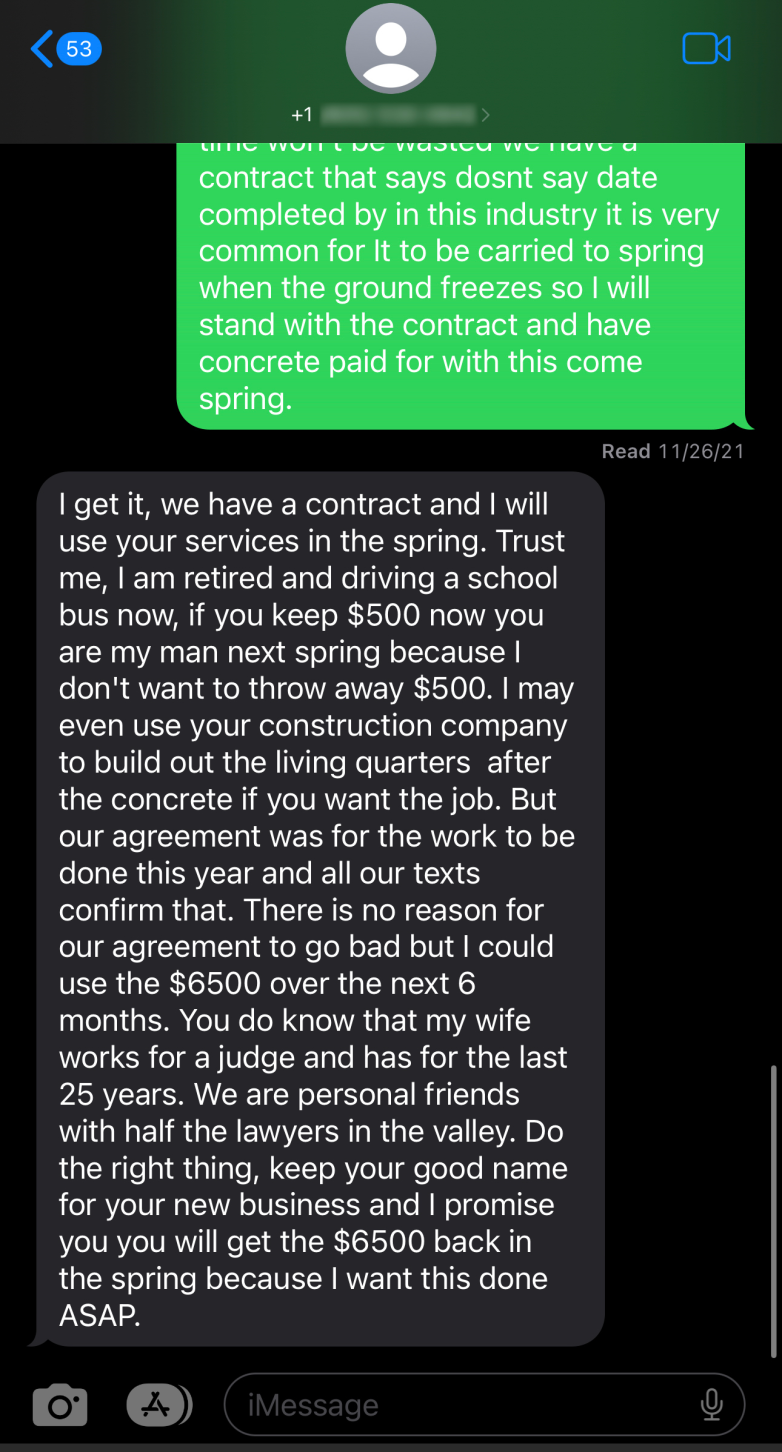

“You do know that my wife works for a judge,” the client texted Barth.

The implication was that McGinnis had used Barth’s criminal case to resolve a civil dispute involving someone the judge knew personally. The Department of Justice opened an investigation into McGinnis’ actions, Wisconsin Watch has learned, but the case has languished for more than a year with no indication whether charges will be filed.

The case shows how Wisconsin judges enjoy limited oversight for their courtroom conduct due to broad legal immunity. It has been decades since the state Supreme Court removed a judge from the bench after the Wisconsin Judicial Commission brought a complaint. Since then 21 judges have faced only public reprimands and temporary suspensions for misconduct in office.

Legal experts agree judges have unparalleled latitude for taking away someone’s liberty, especially if they are on probation. But invoking criminal penalties to compel action in an unrelated dispute arguably goes beyond a judge’s lawful authority.

John P. Gross, director of the Public Defender Project at University of Wisconsin Law School, reviewed the transcripts in Barth’s case and said it’s unclear what the legal basis was for the judge jailing the defendant.

Public records show Barth faced no formal complaints at the time of the hearing, raising questions as to how the judge knew about the cement dispute.

“But even if there was a civil action,” Gross told Wisconsin Watch, “there’s no real justification to use that as a cudgel.”

Barth’s ordeal is only the latest in a series of documented missteps and alleged overreach by McGinnis. Yet to date, the judge has faced no public consequences for his actions.

A reputation as a tough judge with polarizing style

Defense attorneys in Outagamie County offered mixed opinions on McGinnis’ reputation, with one seeing him as a tough-but-fair jurist and others saying he prejudges defendants he doesn’t like.

In Wisconsin, circuit court judges run for six-year terms in nonpartisan spring elections. But no one has challenged McGinnis since his first election in 2005 at age 34. His style as a jurist has come under scrutiny for years. He didn’t respond to Wisconsin Watch’s interview requests.

In 2007, McGinnis began sentencing dozens of nonviolent offenders to work for a nonprofit that salvages and sells fixtures from demolished buildings. The sentences weren’t unusual, but what attracted attention was McGinnis supervised the offenders from the bench, cutting probation officers out of the process.

“I use only nonviolent offenders and they are not necessarily bad people,” McGinnis told the Post-Crescent at the time.

McGinnis’ micromanaging is similar to fellow Outagamie County Circuit Court Judge Vincent Biskupic, whose legally questionable method of tightly controlling defendants’ lives was detailed in Wisconsin Watch’s 2021 series Justice Deferred.

McGinnis’ relationship with the probation department itself has faced scrutiny. After fending off a messy lawsuit from former business partners, he came into ownership of an office building near the courthouse. He arranged a multimillion-dollar deal with the state Department of Corrections to house its probation department in 2008.

The Post-Crescent obtained internal emails showing agency attorneys called the $2.7 million 15-year lease “problematic” as the judicial code of conduct prohibits judges from having a business relationship with entities that come before the court. McGinnis said the Wisconsin Judicial Commission provided ethical guidance essentially green-lighting the deal.

The commission denied a records request for its ethical guidance, citing confidentiality of its proceedings. The 15-year lease was renewed last May and could be worth as much as $4.4 million through 2042.

A complaint alleged McGinnis skirted state ethics law in years past by not disclosing income he received for legal training sessions for Appleton police officers.

Records previously published by Wisconsin Watch show that between 2007 and 2011 he billed the city of Appleton $18,450 for scores of half-day legal trainings at $450 a session.

The revelation came only after an incarcerated man serving a 45-year sentence for child sex offenses filed a lawsuit claiming it was a conflict of interest for a judge to train police officers and then make rulings based on their performance. A federal judge dismissed the suit as frivolous.

In 2009, McGinnis was instrumental in creating a Truancy Court for the Appleton Area School District to deal with chronic absenteeism in secondary schools. Some lauded the criminal justice-style approach to getting wayward teenagers back on track.

But some parents and community members began complaining about what they characterized as his bullying and belittling the minors who would appear in his courtroom — and even exit in handcuffs over attendance issues.

A 2018 outside review commissioned by the school district recommended McGinnis be removed from the program. The review substantiated complaints that he punished students through days-long placements in ShelterCare — a secure housing facility for youth considered to be at-risk.

McGinnis also ordered electronic monitoring despite the Court of Appeals ruling he lacked authority to do so.

“The judge has bullied students who do not communicate easily and their parents,” Madison attorney Duane McCrary wrote in his report after interviewing school administrators, families and judges involved in the Truancy Court. “When parents or attorneys try to explain, he shuts them down.”

The Appleton City Council repealed its truancy ordinance in 2019 and the Truancy Court was subsequently dissolved, ending the decade-long experiment.

Court of Appeals overturns sentences

McGinnis’ actions in criminal cases have also drawn public scrutiny.

A 2015 Post-Crescent investigation found that over a four-year period he led the state in substitutions — 1,130 requests by defense attorneys that he be replaced by another judge in felony cases, which the newspaper said was triple the volume of any other circuit court judge in Wisconsin.

A Wisconsin Watch review of court data over the past five years found McGinnis continues to lead Outagamie County in substitutions, drawing nearly a fifth of all requests out of the seven judicial branches.

McGinnis’ rulings have also been overturned by higher courts for exceeding his sentencing authority. In 2009, an appellate court admonished McGinnis for being “objectively biased” after he threatened a defendant with maximum sentencing if the man violated his probation. The court ruled the defendant was entitled to a new judge and resentencing.

In 2018, the appellate court reversed a six-month contempt sentence that McGinnis imposed when a defendant rolled his eyes and glared at him in a case that attracted scrutiny from legal watchdogs.

“It’s not showing up on a transcript but that’s the type of disrespect that shouldn’t exist in a courtroom,” McGinnis told the defendant. “You can purposely look away, and you can look at me and give me the fuck-you look, right, that you have been giving me for the last minute and that’s fine. That’s just who you are.”

McGinnis said the man could be released only by submitting a written apology and paying a $5,000 fine to the court.

State prosecutors — rather than defend McGinnis’ jail sentence — filed a letter confirming that the six months in lock-up went beyond the 30-day statutory maximum. In all, the man spent 42 days in jail.

The $5,000 fine imposed by McGinnis was also reversed as it exceeded the legal maximum by tenfold.

Judges given broad immunity by highest court

The U.S. Supreme Court has given judges almost blanket immunity for their official actions on the bench. Higher courts can overturn a decision when a judge fails to follow the rules, but judges rarely face sanctions for exceeding their authority.

In Wisconsin, the state Supreme Court can remove a judge based on a complaint-driven recommendation from the Wisconsin Judicial Commission, a mixed panel of appointed lawyers, judges and non-lawyers. Other methods include a public recall and removal by the Legislature via impeachment or address.

Wisconsin judges have been accused of serious crimes — federal felony prostitution charges and even murder in a political rivalry — but when it comes to their actions on the bench only one has been successfully removed.

Former Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle was a private attorney in the 1980s when the Wisconsin Judicial Commission asked him to argue the case against Rusk County Circuit Judge Donald J. Sterlinske, accused of a string of improprieties from falsifying court records to settling personal scores from the bench.

“It was pretty egregious,” said Doyle, who went on to serve 12 years as attorney general and two terms as governor. “There was a whole series of other really intemperate and questionable behavior on his part.”

In 1985, the state Supreme Court agreed to remove Sterlinske for, among other things, using a high bail amount as a retaliatory measure for a defendant who had asked for a different judge.

“He had a little fiefdom in that county, and he was used to getting whatever he wanted by saying he was the judge,” Doyle told Wisconsin Watch.

But records show the commission has since relied on public reprimands and suspensions from a few days to a couple of years for cases ranging from sexual harassment to brandishing firearms in the courtroom.

Most recently, Winnebago County Circuit Court Judge Scott C. Woldt received a seven-day suspension in 2021 for at least twice showing off a pistol and “making crude, sarcastic, and undignified comments” toward defendants as well as “intemperate remarks concerning victims in criminal cases.”

A subsequent complaint was filed after he threatened a defense attorney who had displayed a lawn sign supporting the judge’s opponent in the 2022 election. The commission has not indicated whether it would again sanction him.

Enforcing misconduct laws typically falls to local prosecutors, who may be conflicted in doing so.

“The judge can make … the life of the district attorney’s office hell,” said Mike Balskus, a defense attorney and former prosecutor who practices criminal law across northeast Wisconsin. “(Judicial misconduct) should not be tried in the county where the judge is practicing or making his rulings.”

McGinnis walks back cement contractor’s jail sentence

Barth, the cement contractor jailed by McGinnis over the unspecified debt, didn’t stay locked up for long. Fond du Lac County attorney Kirk Everson received a tip about the matter, ordered the transcript and put himself on retainer the next day.

“It was very difficult to believe,” Everson said later, “because obviously, if you’re gonna take away somebody’s liberty, it’s got to be done legally. And what was described to me, it just sounded a little bit unusual.”

Everson appeared by phone with Barth within 48 hours of the first hearing. McGinnis’ tone had changed, and he quickly walked back the sentence.

“I was reluctant to get into a lot of details in front of a packed courtroom because we had a whole bunch of people,” McGinnis said, according to the Dec. 22, 2021, transcript.

McGinnis said “information” about Barth came to his attention while he was reviewing arrest warrants. He said he became concerned about the positive drug test for marijuana, driving on a suspended license “and this financial issue, or issues, because I think there was a lot more going on than that. But again, I’m a little bit restricted on what I can say.”

It’s unclear how the judge would have learned about the financial dispute in an arrest warrant because the property owners wouldn’t file criminal complaints until two weeks later, according to police records.

Legal experts agree judges can’t jail someone unless the person is found in contempt or on the recommendation of the probation officer for specific violations.

“You are entitled to a hearing on whether or not you did, in fact, violate the terms and conditions of your probation,” said Gross, the criminal law professor who reviewed the transcripts. “But that didn’t happen here.”

Once Everson, the defense attorney, started asking McGinnis about the legal basis for his client’s incarceration, the judge walked back the 90-day sentence.

“When I asked him, ‘Why are we here? Why is Mr. Barth incarcerated?’ — I don’t believe I was ever answered,” Everson said later. “But he was released that day.”

The court record doesn’t provide much clarity to legal observers.

“I don’t want to be unnecessarily overly critical of a judge,” Gross said. “It’s like a word salad in there about why he did what he did.”

The couple who hired Barth may have had a good case for wanting their money back, but Gross said the judge’s apparent merging of a civil dispute with a criminal procedure was problematic. Congress abolished debtors’ prisons in the 1830s.

“There’s a legitimate way to deal with this,” Gross said. “If he was liable in the civil matter for a breach of contract — that’s not a reason to revoke his probation in criminal court. He didn’t commit a new crime.”

What’s also potentially problematic for McGinnis is if he had used his authority over a criminal matter to settle a dispute on behalf of someone he knows.

“You do know that my wife works for a judge,” property owner Wayne Dorsey wrote in a Nov. 26, 2021, text to Barth demanding a refund. “We are personal friends with half the lawyers in the valley. Do the right thing and keep your good name for your new business and I promise you you will get the $6500 back in the spring because I want this done ASAP.”

Barth told Wisconsin Watch he didn’t take it very seriously, but he realized he might be in trouble when he saw Paula Dorsey — who works for a different Outagamie County circuit judge down the hall — in the courtroom as McGinnis threatened him with jail.

Everson filed a motion asking McGinnis to recuse himself from Barth’s criminal case because of his connection to Paula Dorsey.

Everson quoted from the judicial code of conduct in his Jan. 6, 2022, motion: “A judge may not lend the prestige of judicial office to advance the private interests of the judge or of others.”

Wisconsin Watch requested courthouse emails between McGinnis and Dorsey involving the Barth case. In Wisconsin, judges are the custodians of their own records.

McGinnis produced only his own emails with the head of the Wisconsin Judicial Commission seeking guidance on the recusal motion. The correspondence indicates McGinnis laid out the situation over a voicemail he left with the commission’s director.

Judicial Commission executive director Jeremiah Van Hecke wrote back March 3, 2022, reassuring McGinnis could hold onto the case unless he has a “close relationship” with the courthouse employee, is a witness to the dispute or is the employee’s direct supervisor.

“I do not see a clear basis for recusal,” Van Hecke replied.

McGinnis denied the motion and Barth continued to appear before him for regular probation review hearings over the next seven months.

Van Hecke declined to comment.

Barth pays back every penny

Barth said while in jail he was confused about the prospect of spending the holidays behind bars. He said his outlook changed following an unexpected jail visit from Everson, the defense attorney.

“It was this big dude with a white beard,” Barth would recall later. “It was a Christmas miracle.”

But Barth’s legal worries weren’t over. The Dorseys filed a complaint with the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. Barth settled it by — among other things — agreeing to clearly state on contracts when jobs would be started and completed. The Dorseys also reported Barth for fraud with the Grand Chute Police Department after police in Hortonville declined to intervene.

“I explained to Paula this is a civil matter,” Hortonville Police Chief Kristine Brownson wrote in her summary. “Paula asked if I was going to make contact with Tyler concerning the money. I told Paula I would not be.”

Grand Chute assigned a detective who attended Barth’s April 7, 2022, probation hearing to oversee the couple receiving the remainder of the $7,000 deposit. The case, investigated as suspected fraud, was then closed as a civil matter.

Barth’s probation officer Shannon Hein reported to McGinnis on Aug. 10, 2022, that the financial dispute had been settled.

“Ms. Dorsey confirmed that Mr. Barth returned her deposit in full so the situation has been resolved,” Hein wrote, adding that no other consumer complaints were outstanding against the contractor.

“Sounds like a good report,” remarked McGinnis in a handwritten note in the margins, adding instructions to call and see if additional probation review hearings would be needed.

Reflecting later, Barth said there was so much pressure he eventually paid back every dime, leaving him out the time and money he put into the job.

“I washed my hands of the whole thing,” Barth said. “I just want to run a business.”

For his part, Wayne Dorsey denied the suggestion that his wife pulled strings at the courthouse to help get their money repaid.

“My wife doesn’t even work for Judge McGinnis,” Dorsey told Wisconsin Watch by phone. “I’m not even sure how we got the money back. But we did.”

He said he wasn’t sure if his wife was in the courtroom the day Barth was jailed over the financial dispute. Paula Dorsey referred all questions to her attorney, who did not respond.

State criminal investigators open probe

DCI investigators have interviewed Barth and his attorney over the probation case, but their last contact was more than a year ago and they haven’t heard anything since.

Barth’s defense attorney — who Barth said took the case for free — asked investigators to read the transcripts for evidence of misconduct.

“When I talked to the district attorney, it was obvious that they were going to have a conflict, and so was all (local) law enforcement,” Everson said. “So that’s when the referral would go to DCI.”

Outagamie County District Attorney Melinda Tempelis confirmed her office had recused itself. She referred questions to the state Department of Justice.

State investigators refused to comment on the McGinnis investigation or the limits of its jurisdiction in pursuing public integrity cases.

Assistant Attorney General Paul M. Ferguson of the Office of Open Government denied a records request for its McGinnis file, explaining the files “pertain to an investigation that is continuing at this time,” but wrote that they could be available in the future.

Meanwhile, Barth hasn’t completely put his experience in McGinnis’ courtroom behind him.

“If there’s anything that I would like to see,” Barth said, “is he can’t do that to no one else.”

Barth has retained Madison civil rights attorney Jeff Scott Olson to pursue a potential civil action. But Olson concedes it’s very difficult to hold judges accountable.

“For something he does with his robe on, it is almost completely impossible,” Olson said.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Want More Local News?

Civic Media

Civic Media Inc.

The Civic Media App

Put us in your pocket.