Op-Ed

Joy and Desperation in the Fox Valley

It’s one of the swingiest regions in the state, a microcosm of Wisconsin’s changing political landscape. Can Democrats win there in 2024? A special feature story from The Recombobulation Area.

Driving along a rural, two-lane road in the Fox Valley in Wisconsin, past farms and churches and roadside taverns, Emily Tseffos is telling me how this campaign is “slowly restoring my faith in humanity.”

“Minds are changing,” she said of people’s politics in this part of the state. “It’s ripe for the picking on either side.”

The Fox Valley is located in eastern Wisconsin, encompassing much of the area surrounding the upper and lower Fox River. It’s an area that’s experiencing colliding forces of shifting political trends and economic and cultural change, and in many ways, embodies a microcosm of much of the state of Wisconsin, from rural farms to walkable urban centers to the mid-size cities and villages on rivers and lakes that dot the Midwest.

Tseffos is the Democratic candidate running in Assembly District 56, a deep-red part of the Fox Valley that includes parts of Outagamie and Waupaca counties, and cities like Greenville, Hortonville, New London and Shiocton. The partisan lean of this district favors the GOP by a 30-point margin. It is a long-shot race. But Tseffos is on a mission. She is trying to get to more than 3,000 doors in the district, she is putting miles on her minivan every day, and she is putting pressure on the longtime incumbent, David Murphy, who she feels has been out of touch and unresponsive to constituents. I met with Tseffos 18 days from Election Day, and it seems like the mission she’s on is less for those 18 days, more for the next 18 years.

“This district is not going to go for Harris,” said Tseffos, who is also the chair of the Outagamie County Democrats. “There’s no way. But I’m hopeful that these efforts and the way we’re working on this campaign is going to show that we’ve outperformed expectations and that we’re building on that for the next round. This isn’t over in November…Flash in the pan politicking doesn’t work for a lot of people. We need to get back to understanding that. We’re going to show up for you again and again and again.”

Going door to door in rural areas can be a cumbersome process. Going from one house to the next can involve a short drive each time, people might not always be home or willing to talk. But Tseffos approaches each door with an inviting sense of humor, a remarkable earnestness and genuine bravery.

“I’m here talking about politics at your front door, just what everyone wants!” Tseffos will say when introducing herself. She talks about finding common ground. She talks about how the top of the ticket might be different than where she is, running at the bottom. For many of the doors she knocks on, they’ve never seen a Democrat show up before.

“A large part of this district has never been touched by a Democrat running,” she said. “But you talk to people, and you find out — and I tell them at their doors, too — we’re being manipulated by people at the top to create outrage, to put people in a box that is either far left or far right. And that’s not where most of us live. We have to get back to having conversations that are sometimes hard, and sometimes you’re going to come to an impasse. But for the most part, people care about their family. They care about their community. They care about their country.”

Tseffos will also walk right up to these doors, and after talking about finding common ground, will mention that part of the reason she got involved in politics is because she is a “victim of sexual violence.”

“A big part of it for me is because we’re trying to humanize a candidate, we’re trying to humanize a party or the ideology behind it, (making) yourself vulnerable in a way that isn’t typically done politically,” she said. “In those moments of saying, yes, I’ve experienced this, it shapes how I view legislation about it. It allows them to open up in a way that maybe they haven’t either.”

She tells the story of meeting with a devout Catholic woman at her home, who opened up to her about her own experiences.

“She said, ‘I had a miscarriage and it was coded as an abortion, and it was so shameful for me. But I understand why you cannot ban abortion outright,’” Tseffos explained. “To connect on that human level is just paramount when it comes to building trust with people politically.”

There are now “Emily for Wisconsin Assembly District 56” signs next to Trump signs in front of homes in the rural Fox Valley.

“I know that the only way to break through the noise as far as the hyper-polarization of the two parties is to show up and humanize myself on their front door,” she said. “So, that’s what I’ve been spending most of my time and energy doing. I don’t shy away from any door.”

If Democrats win in the Fox Valley this year, it’ll be because “we outwork them and we win,” said Tseffos. That work, that ground game has the power to impact the future of the entire country.

This could be the place that decides who wins in Wisconsin, and with it, determines the fate of the nation.

Wisconsin has been the tipping point state in the last two presidential elections. Four of the last six presidential elections in the state have been decided by a less than 1% margin. It almost seems inevitable that Wisconsin be right at the center of the Electoral College map once again.

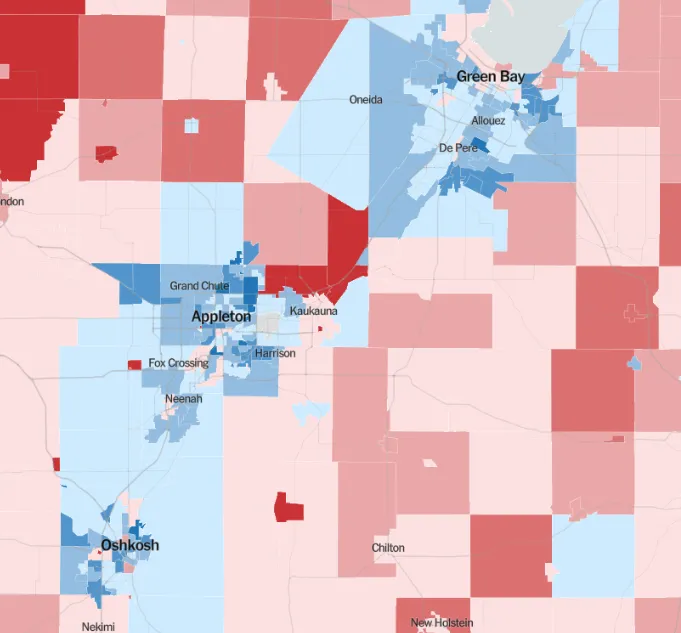

While Wisconsin has remained as one of the nation’s true swing states from 2000 to 2020, the way in which it gets to that near 50-50 split has changed significantly. In 2000, when Al Gore won the state by about 5,700 votes, Democratic support was more spread out, particularly in western Wisconsin, and Republicans ran up huge margins in the suburban counties surrounding Milwaukee. In 2020, when Joe Biden won by just over 20,000 votes, Democrats narrowed the GOP’s margins in the suburbs, countering Republicans’ growing support in rural areas.

That’s been part of a familiar narrative that’s emerged in the Trump era. In 2016, many focused on the “Obama-Trump voters” and the realignment among white voters without college degrees who opted for Trump over Hillary Clinton and have largely been voting Republican since. By 2020, the suburban shift toward Democrats that had been so prevalent around the country in the Trump years officially took hold in the WOW counties — Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington — and supercharged Democratic margins in Dane County.

But this narrative can often overlook one of the swingier regions in the state, a place home to hundreds of thousands of voters — the Fox Valley and Green Bay.

The three critical counties in this region have been dubbed the BOW counties, a riff on the WOW counties, which includes Brown (home to Green Bay), Outagamie (home to Appleton) and Winnebago (home to Oshkosh) counties. What people might not realize, given how much more often the WOW counties are dissected, is that each of these three-county regions have roughly the same combined populations – just under 650,000. That’s a lot of votes.

And these are indeed swing votes, in a region with a fiercely independent streak. In 2018, Sen. Tammy Baldwin won a majority in each of these counties, but so did then-Gov. Scott Walker. People in the Fox Valley can be wary of both parties, often voting based on the individual.

In more recent years, too, we’ve seen these counties go either way in statewide elections. In 2023, they each went for now-Justice Janet Protasiewicz, the liberal candidate in the critical Wisconsin Supreme Court race, over right-winger Daniel Kelly. In 2022, a year that saw split results in Wisconsin with Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and Republican Sen. Ron Johnson each winning re-election, all three counties went majority Republican in both races. The same was the case in 2020, with Trump winning each of the three critical counties.

But Democrats in 2020 made key gains in the region, narrowing the margin of victory in each county. Let’s take a look at what’s happened in each of these three counties (all according to data from Marquette University).

Brown County:

- 2016: Trump + 10.7%

- 2020: Trump + 7.2%

Outagamie County:

- 2016: Trump + 12.6%

- 2020: Trump + 9.9%

Winnebago County:

- 2016: Trump +7.3%

- 2020: Trump +4.0%

In a state that was decided by 20,000 votes either way in both of these elections, these gains are critical — and perhaps indicative of larger trends.

The political environment in the Fox Valley is one of competing shifts. Rural areas in the region are undoubtedly getting redder, and one can point to the decline of manufacturing jobs — at paper mills, especially, a bedrock of this particular area for decades — as key in accelerating certain aspects of that shift, particularly among those who do not have college degrees.

But that alone would be an oversimplification of what’s happening in the region, which doesn’t fit in a convenient rural-suburban-urban dynamic. There’s no Milwaukee-sized population center to make many of these blue-shifting communities seem especially “suburban” or “urban,” but that belies much of what people get wrong about Wisconsin, and where these more mid-sized communities and others like them are shifting politically.

In 2018, when Scott Walker lost to Tony Evers, it wasn’t just due to Republicans’ eroding support in the Milwaukee area suburbs, it was that “Walker lost ground in every community in Wisconsin of more than 30,000 people,” Craig Gilbert, then of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, noted at the time. That trend has continued in the years since.

Take a look at just a few of the shifts in these mid-size cities in and around the Fox Valley, looking at gubernatorial elections in 2014 (where Republican Scott Walker defeated Democrat Mary Burke) to 2022 (where Democrat Tony Evers defeated Republican Tim Michels).

Menasha (population: ~18,000)

- 2014: Walker + 2.8%

- 2022: Evers + 7.0%

Neenah (population: ~28,000)

- 2014: Walker + 8.2%

- 2022: Evers + 9.7%

Oshkosh (population: ~66,000)

- 2014: Burke + 1.5%

- 2022: Evers + 13.7%

Appleton (population ~75,000)

- 2014: Walker + 5.9%

- 2022: Evers + 16.4%

Green Bay (population ~107,000)

- 2014: Walker + 2.8%

- 2022: Evers + 12.3%

Vote by vote, election by election, the primary population centers of the Fox Valley have been becoming more and more Democratic. But trends are not always linear. And Trump has traditionally driven higher turnout among those who do not always vote, and Republican margins in rural areas continue to grow.

So, that begs the question: Can Democrats win in the Fox Valley and Green Bay in 2024? I spent a few days there to find out.

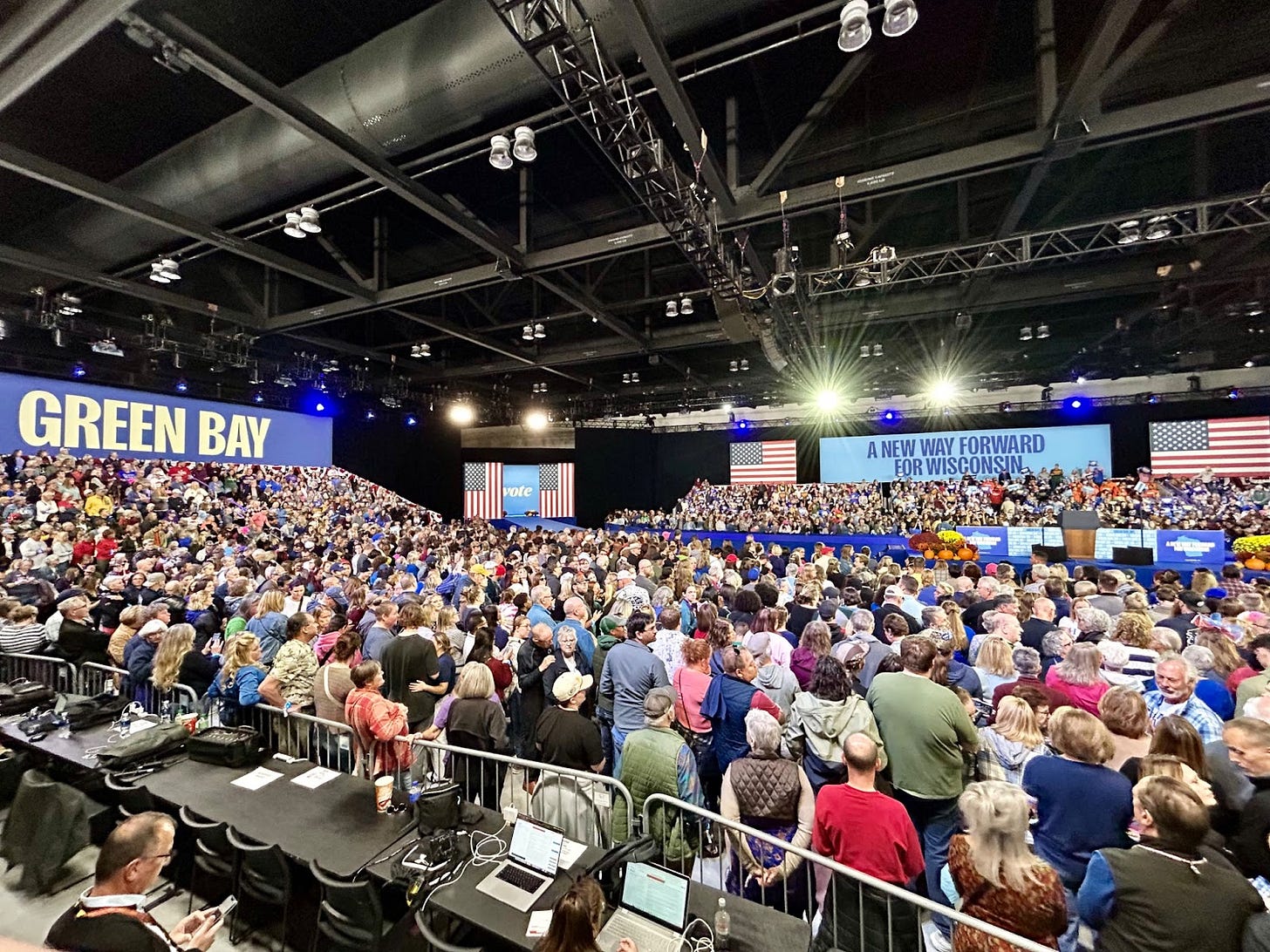

It was mid-day Friday in Green Bay, and the Brown County Democrats’ office was bustling with activity. People were checking in for canvassing shifts, picking up yard signs, hunched over laptops, poring over maps stuck to the walls. The night before, Kamala Harris held a rally in the city at the Resch Center, just across from Lambeau Field, and the Democrats there were still buzzing from having 4,000 people fill the center to see the Democratic nominee up close and in person.

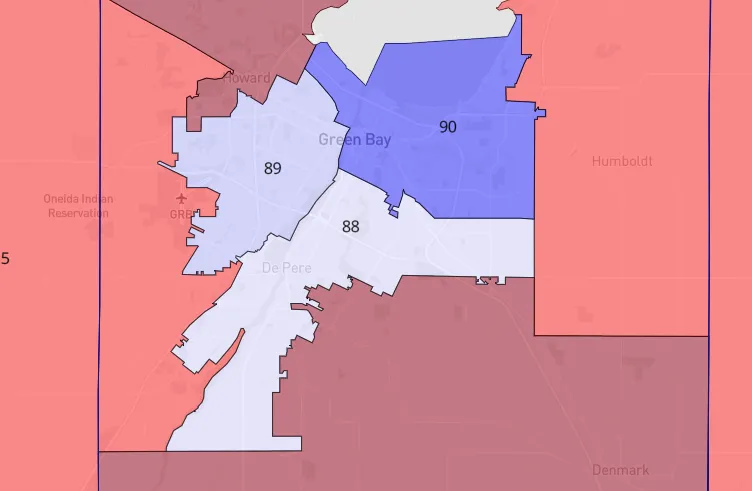

I was there to meet with two candidates for State Assembly — Ryan Spaude (running in the 89th) and Christy Welch (running in the 88th). We sat down at a table in the building’s basement, in a wood-paneled room that felt much like any church basement you might find in the region.

I asked Welch about how she was feeling the day after the campaign rally.

“I heard a phrase last night that I like,” she said. “I was saying ‘cautiously optimistic,’ but now ‘nauseously optimistic.’… That’s a better summary of my feelings. You obviously don’t ever want to take anything for granted based on how you’re feeling. And there’s not a ton of real-time data to be able to look at. So we’re just nauseously optimistic, doing what we need to do.”

Earlier that morning, a few blocks away, I’d met with Kristin Lyerly, an OB/GYN who is running for Congress, at a coffee shop on Broadway. She’d been one of the speakers at the Harris rally the night before, stepping out to a huge ovation. She talks about people being ready for this moment, comparing it to Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign, “but,” she adds, “with a hint of desperation.”

The nausea in the optimism, the desperation in the joy. Green Bay area Democrats understand all too well just how precarious this moment is for their community, and for the state at large.\

In the area, there is an open seat within an open seat, like a Russian nesting doll of nailbiter races. It’s not just the top of the ticket with Harris-Trump or Baldwin-Hovde that’s drawing attention in and around Titletown and the endless number of campaign events that have descended upon the area, it’s what’s happening down-ballot, too.

Lyerly is running in the 8th Congressional District, which is an open seat after Mike Gallagher resigned in April. She faces Republican political newcomer Tony Wied, who won his primary on the back of a Trump endorsement. State Senate District 30, which includes Green Bay and surrounding Brown County communities, is also an open seat race after incumbent Republican Eric Wimberger moved to run in much more red-leaning District 2. There, Democrat Jamie Wall faces Republican Jim Rafter. And all three of the Assembly districts within that Senate district are also open seats. Democrat Kristina Shelton is not seeking re-election in the 90th, Republican John Macco is not seeking re-election in the 88th, and in the 89th, Republican Elijah Behnke was drawn into the 6th District and is running for re-election there. It’s an almost entirely clean slate.

The 8th Congressional leans red, the 90th Assembly leans blue, but the State Senate seat and the other two Assembly seats are bonafide “toss-up” races. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that the road to the Assembly majority goes right down Lombardi Avenue.

“It’s crazy having so many targeted races in one spot, but our teams, as you can tell, are working together,” said Spaude.

There’s a new degree of organization, cohesion, and unified effort unfolding in the area. Two years ago, there was no Democrat even running in the congressional race. Now, Lyerly started her run early, and has been part of the candidate recruitment efforts down-ballot throughout the district, and there’s now a Democrat running in every Senate and Assembly race in the region — even in some of the deep-red rural districts. Many of these candidate are women. “Breaking the gerrymander,” Lyerly said, has been a huge factor in the region.

“In northeastern Wisconsin, two years ago, a third of the seats went totally unchallenged; we didn’t even have Democrats running, so Republicans just ran roughshod over the entire district,” said Lyerly. “Now, we’ve got candidates running in every single one of those seats, and they are enthusiastic. They’re well supported, they’re connected, they’re knocking doors, they’re doing the fundraising. The party is investing in them, and the Republicans aren’t out doing the campaigning, having the conversations, the way that the Democrats are.”

Spaude said Lyerly has played an important role in connecting many of these campaigns.

“Dr. Lyerly has been a glue, a bond that’s keeping a lot of us together,” said Spaude.

Many of these down-ballot races in the region beyond Green Bay are also changing in significant ways because of new maps. Along with the toss-up Senate and Assembly races in Green Bay, this year could be the first time in nearly a generation that a Democratic state senator could be elected in the Fox Valley, and there’s potential for a Democrat to win in the Neenah/Menasha area to join Democratic incumbents from Oshkosh and Appleton.

Lee Snodgrass, state representative from the Appleton area who is also part of the Democratic leadership in the Assembly, said that the issue of fair maps is one that stood out as a top issue in the 2023 Wisconsin Supreme Court race.

Having someone on the court who is going to support fair maps “was the biggest thing,” she said. “Everybody has kind of known that until we have a game board that’s fair, we’re just spinning our wheels.”

Is there pent-up energy for these races, then?

“Very much so, yes,” she said emphatically. “Once the new maps were here, people were really re-energized to try and do everything that they could.”

One of those candidates that took the plunge to run for office with these new maps is Duane Shukoski, the Democratic candidate in Assembly District 53, which now includes all of both Neenah and Menasha. He is a political newcomer, and previously worked at Kimberly-Clark and was a member of the union there for nearly 40 years, specializing in environmental leadership roles.

“I had a great union job,” he said. “We bought a new house, had a couple cars, took our young boys down to Disney. You know, the American dream, right? It’s unfortunate that it’s not like that today.”

For Shukoski, new maps that could cut through the dysfunction in state government in Madison were a big reason that led to his decision to run.

“For the longest time, the party in Madison was picking their voters with those gerrymandered maps, and now we finally get to pick our legislators.”

He added, “In Neenah and Menasha, we’re together again; we’re a cohesive unit again. It’s been broadcast around the country that we were the most gerrymandered state in the union. And that’s not Wisconsin fair. It’s just…how did we get here? Well now I’m here, and I can be part of the solution…I know I could represent us in a much different way, and in a much more fair and honest (way), with some integrity, bringing those things back to Wisconsin that I thought were always there.”

In this race, Shukoski is facing someone with far more political experience — Dean Kaufert, who was the mayor of Neenah for eight years, and previously served in the Wisconsin State Assembly from 1991 to 2015. He was recruited heavily to run by Republican leadership, and this has been another effect of the end of Wisconsin’s gerrymander. The Republican candidates running in more competitive races have more elected experience or have more of a moderate political record.

But at a recent public forum, Shukoski — the youngest of 13 children, who grew up in foster care from the age of three on, and has recently volunteered with an organization that works with unhoused people in Appleton and around the valley — became frustrated by Kaufert’s comments about those less fortunate.

“(Kaufert) said, ‘Yeah, the poor, they’ve got 70-inch screen TVs, they’ve got tattoos, they’ve got cigarette butts.’ It’s like he was looking down his nose. How abhorrent is that? When you don’t know what happened to that person to get to that point, you don’t know if something happened in their life, you don’t consider any of that. It hurt me personally when he said that. That’s not how I think about the poor. They need help.”

This is one of a handful of races that could determine the Assembly majority under new maps this year.

Spaude and Welch’s races in the Green Bay area fit that description, too. In fact, the numbers suggest that these two races are smack dab at the center of the fight for 50 Assembly seats. The 88th, where Welch is running, was won by both Tony Evers and Ron Johnson two years ago in the midterm elections. In the 89th, where Spaude is running, Evers won, too, and Mandela Barnes barely carried the district.

Welch is the chair of the Brown County Democrats, and even before the decision from the Wisconsin Supreme Court came down in December, striking down the previous maps, she and the county party had been building the infrastructure and laying the groundwork to be ready for a new landscape.

“So, when we got the new maps,” said Spaude, “we were ready to rumble.”

The district Spaude is running in used to include the western shore of Green Bay, running north to Marinette at the border of Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Now, it’s entirely contained within the Green Bay metro area, including the western part of the city of Green Bay, and all of Ashwaubenon — another mid-size city that’s been shifting toward Democrats in recent years (GOP+20 in 2014 to GOP+4 in 2022).

Spaude is an Assistant District Attorney in the Brown County District Attorney’s office. He’s young and enthusiastic, and speaks deliberately but energetically. He understands the election data in the region well, and understands how competitive so many of the districts in the region are.

“Green Bay is a Democratic city,” he said. “Folks in Madison or Milwaukee, they think anything north is red. But this is a Democratic city.”

And the suburbs, he added, are becoming more Democratic.

“From 2018 to 2022, the movement in our districts toward Gov. Evers was greater than the state overall,” he said. “The data does back it up. The suburbs are moving our way.”

The bluest of the three Green Bay area seats is District 90, where Amaad Rivera-Wagner is running to be the new Democratic representative. He has worked as the chief of staff for Green Bay Mayor Eric Genrich for several years.

In this role, he’s had to face all sorts of wild election-related conspiracy theories surrounding the results of the 2020 election. There was a “Stop the Steal” rally outside Green Bay City Hall on Jan. 6, 2021, former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman called for the mayor’s arrest as part of his sprawling, multi-million dollar review of the election (which produced no evidence of widespread fraud), and Rivera-Wagner and his husband faced a host of insults and very real threats over the past several years.

“In a pejorative way, they kept calling me the diversity director,” he said (Rivera-Wagner is Black and Latino). “They said I worked for Mark Zuckerberg. They stopped my husband at the hospital because they thought I made him up, that I was a paid DNC operative to come to Green Bay to steal the election. They vandalized my car. My tires were popped. We had to talk to the FBI. We had to get police protection. We live in a community that has basically no crime, and we had to get an alarm system, but not from actual criminals, but from right-wing conspiracy theorists who are stalking me and my husband.”

That type of environment was pervasive for years, he said, but has been changing. In the nine months since the new maps were passed, said Rivera-Wagner, the conversation around Green Bay has changed from one dominated by right-wing conspiracy theories about the 2020 election to instead trying to compete on issues that have majority support from the electorate.

“It happened so fast how lines changed realities,” he said. “All of a sudden, you had to start talking to voters… This is the most I’ve ever seen people actually campaign on both sides of the aisle, where some people have to have real conversations. I mean, we have Republicans running on reducing the cost of health care…As someone who watched for three years, the state legislature (hold) hearings and try to arrest the mayor (of Green Bay) for “stealing an election,” to now having people talking about the reduction of health care costs across political spectrums, it almost feels like whiplash. But, it’s welcomed.”

Rivera-Wagner was born in Massachusetts and was raised by a single mother, and experienced homelessness growing up, living in cars and shelters. Despite the challenges he’s faced in recent years, he has glowing things to say about living in Green Bay.

“This place feels like a dream,” he said. “My neighbor bakes me cookies every Christmas. When we walk our dogs, people put out bowls of water that say “We love your pets.” I know this sounds so cheesy, but I feel like I’m living in a movie here. So, I think that’s worth protecting.”

Rivera-Wagner mentions that Green Bay has “less than 1% unemployment” and is actually much more diverse than some might realize — moreso than Madison, he notes — with both existing and growing populations of people of color, “mostly AAPI, indigenous and Latino folks,”

“What’s incredible about this community that I think people don’t get — aside from us having an NFL team, the smallest city to have an NFL team — is that we are this incredibly diverse community that in many ways has been a bellwether for the changing shifts of politics…People are moving to the city and we are bursting at the seams.”

In 2023, U.S. News and World Report ranked Green Bay No. 1 in its list of the Best Places to Live in the United States.

Now, it is perhaps the No. 1 most important place on the map for determining the outcome of the 2024 election, from the top of the ticket on down. If Welch, Spaude, Rivera-Wagner, and State Senate candidate Jamie Wall emerge victorious on Nov. 5, that could very well mean the State Assembly has flipped for Democrats for the first time since 2008, and that Tammy Baldwin and Kamala Harris will have won the state of Wisconsin.

At the rally in Green Bay, enthusiasm was tremendous. I talked to a handful of people who had traveled far, noting the many Trump signs in their hometown. During Harris’ speech, the fourth I’d covered to that point, I noticed how the Green Bay audience was more attentive and tuned in to the details of what she was saying, particularly in moments when she’d discuss policy. When Harris spoke about her proposal to broaden Medicare coverage of home care, you could hear a pin drop. People wanted to hear those details, the kinds of things that can be lost in the blitz of campaign ads and partisan rhetoric. And the applause moments and the “We’re not going back!” chants were still as loud as any I heard at rallies in West Allis, Milwaukee and at the DNC in Chicago. But I almost didn’t make it to this rally in time.

The drive along I-41 features a whole lot of billboards that are somewhat iconic in their own right. From the billboards for sex shops next to fire-and-brimstone religious signs to the Bergstrom Auto signs with the Green Bay quarterback and head coach, to the latest addition — endless signs for legal cannabis available in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — it’s a quixotic staple of any kind of drive through the region. This year, not surprisingly, it’s an especially political edition of the billboard game.

But along this drive, you can see that there’s a gulf, of sorts, in between Appleton and Green Bay. Green Bay might be located on the Fox River but most wouldn’t necessarily say it’s part of the Fox Valley or the Fox Cities. They have some broad similarities in northeastern Wisconsin, but they are part of different ecosystems.

And as I made it through Grand Chute and Kaukauna and hit the especially rural stretch of Outagamie County, everything stopped. There had been construction up and down I-41 that had been pinching traffic every day, but nothing quite like this. I rolled to a dead stop and tried to figure out what was happening and my phone’s GPS app was directing me to get off the highway at an upcoming exit.

All cars were being directed off the highway, and law enforcement sent all cars on an unclear detour along a nearby frontage road. Eventually, I’d learn that a crash and a car that caught on fire had caused a six-mile backup on the highway. And making my way north, I’d come upon this sign.

A Trump sign on a detour caused by a car in flames just before the Freedom exit on the way to the Kamala Harris “New Way Forward” rally seemed just too on the nose for the moment. The metaphor is just entirely too overt. Like the path forward was always leading us there, the nation’s promise of freedom and a bold new era sidetracked by the foreboding fireball that is Trump.

Maybe it’s best just to move on. I did make it to the rally just in the nick of time, after all.

An appetite for bipartisanship

The afternoon before the Harris rally in Green Bay, I went to the office for the Democratic Party of Outagamie on College Avenue in Appleton to meet Kristin Alfheim, the candidate running in Senate District 18 to be the first Democratic state senator in the Fox Valley since before the gerrymander was installed.

Alfheim’s yard signs are purple, and that’s intentional. Knocking doors in the neighborhood around the county party’s office, she talks about whether you lean red or blue, “there’s a little bit of purple in every issue.”

This gets at something that showed up in interview after interview with candidate after candidate in the Fox Valley and Green Bay. There’s a tremendous appetite for bipartisanship in the region.

Alfheim says that in conversations on doors, “If you can get anybody past their number one issue, it almost always goes back to: I wish we could just go back to getting things done.”

But perhaps that’s already starting to change, in no small part because of the new maps and the evolving political environment in Madison.

“Even if you look at the end of the last (legislative) session, there was more movement at the end of the last session than there’s been in a long time,” said Alfheim. “So, why? What caused that? The fact is they were going to have to show up and have to earn those positions. Well, imagine that. An elected official having to earn the position and hold the position. And you hold the position by action, not by having more people gerrymandered into your district.”

This appetite for bipartisanship, and actionable bipartisanship, becomes apparent in a number ways among candidates throughout the region, several of whom have switched parties in recent years. Spaude is a former Republican, and he interned for former congressman Reid Ribble for several months.

Asking Shukoski what he’s heard from talking to people on doors in Assembly District 53, he said “First and foremost: bipartisanship. They are sick and tired of this fighting, this bickering, the way they’re treating each other in Madison.”

The bipartisanship message is “huge in this area,” said Snodgrass.

Several people I talked to also referenced the recent event held in Ripon, Wisconsin, with Liz Cheney endorsing Kamala Harris. While some on the left have been critical of this type of embrace of a former political opponent, people in the Fox Valley and Green Bay spoke of it in reverential terms. Perhaps that event created a sort of permission structure for wary Republicans to not just sit out the presidential race in opposition to Trump, but to take the next step to vote for Harris.

That’s what happened with Republican State Sen. Rob Cowles, the longest-serving state senator in Wisconsin, who said that he would be voting for Harris in the presidential election, saying that this was “one of the most important things I’ve done.” He has served in the Wisconsin State Legislature for 42 years.

(That story was an exclusive from Civic Media’s “Rational Revolution,” hosted by former Brown County GOP chair Mark Becker, who is now a part of Wisconsin Republicans for Harris-Walz. Alfheim was one of the original hosts of that show.)

No episode found

The Trump appeal and the Fox Valley’s changing economy

Part of the post-2016 narrative about regions like the Fox Valley was about that of communities that were left behind — the “economic anxiety” of it all. And while that element is perhaps overstated (and certainly a loaded phrase, at this point), voters in the region did shift significantly in a way that benefitted Trump greatly. From 2012 to 2016, each of the BOW counties shifted between 8-10% toward the Republican candidate.

Major elements of Trump’s 2024 campaign have been more like his 2016 campaign. Bringing the Teamsters president to speak at the first night of the RNC in Milwaukee is among the prime examples of this. He’s clearly going for a certain demographic, and one that powered his 2016 victory — those Obama-Trump voters in the Midwest.

The Fox Valley seems like the type of place this message might resonate. But much has changed between 2016 and 2024. And we all experienced four years of Trump actually being president, and not delivering on promises to do things like revive manufacturing in states like Wisconsin, where his biggest project was the cataclysmic debacle that was the Foxconn project in Racine County.

But the appeal with Trump, at least as it applies to the economic concerns of the Fox Valley, may have more to do with the same type of outsider appeal that made him successful here eight years ago. There is a prevailing “both parties suck”-type of mentality in the region that makes people gravitate to those who want to shake up the system.

Gordon Hintz is a former Democratic state representative from Oshkosh and the Assembly minority leader from 2017 to 2022, who now works with the Wisconsin Laborers District Council, and he says that even if Trump’s policies during his presidency didn’t match the rhetoric of his 2016 campaign, there are still many who will support him.

“There’s been a market for people who felt left behind by the economy and who are frustrated by a government that they felt has never been there for them,” said Hintz. “And specifically this time, it’s impossible to look at things without looking at pre and post pandemic, even with the economy alone. People (might say) they were better off four years ago, before the pandemic, before inflation, before things cost a lot — ignoring a lot of context. That’s where some other people are landing, as well.”

Hintz said inflation is a “global phenomenon and no one has managed it better than the Biden administration.” But, he added, “It’s a typical Democratic issue where, if it takes you three sentences to explain it, it’s no good.”

Tom Nelson has served as the Outagamie County Executive since 2011, a period that’s included a lot of economic change in the region, a shift that’s gone from a manufacturing-centered economy to one more diversified, with growing professional services and health care sectors.

“The transition between economies has been smooth,” said Nelson. “It hasn’t been drastic. It’s not like we’re a one-company town where you have a plant shut down and it just pulverizes the local economy. We’ve seen a shift away from larger plant manufacturing firms to smaller firms. Up and down I-41, it’s just dotted with these types of business parks and industrial parks.”

He added, “Across the board, with the exception of 2009 and 2010, we’ve probably had unemployment at or lower than 3.5% to 4%. So, I think how this community has transitioned has made a really big difference compared to other communities that have been more dependent on, say, one manufacturing plant.”

The paper industry, which has long been central to the regional economy, saw some significant change in the 2010s — some of which Nelson documented in his book, “One Day Stronger,” that he released while running for U.S. Senate in 2022 — and plants did close, but that hasn’t crippled the region, and it’s still a key component of the area’s economy.

“We’re in the part of the paper valley,” said Snodgrass, who used to work for Fox River Paper Co., “and we still have manufacturing centers here — Kimberly-Clark’s mills in Neenah, Appvion in Appleton, we still have mills in Kaukauna. But paper is paper. People don’t use it as much anymore, so that has definitely changed.”

But, she said, other manufacturing companies are still growing in the region, and Hintz adds that the building trades have a “tremendous amount of work, especially with infrastructure projects” that have come from the Biden administration.

“We have globally recognized manufacturing companies in the Fox Valley employing thousands of people,” said Alfheim. “And we have more small businesses than probably most districts. The entire corridor is packed with small businesses.”

The sting of inflation is still here in the region, and housing prices are a growing concern. But the narrative of some hollowed-out former manufacturing center does not fit the Fox Valley. In many ways, the region is thriving economically. And so perhaps, some of the issues driving people to Trump are more cultural. Or, perhaps not.

“The gals, the gays and a few good men”

The nature of the campaign ads in Wisconsin for this election year has leaned heavily into anti-LGBTQ attacks. There have been many disgustingly transphobic attack ads, along with some not-so-subtle jabs at Tammy Baldwin, the first openly gay senator elected to the U.S. Senate, that go out of their way to mention her “partner.”

These ads have dominated the airwaves in the battleground state in the weeks and months leading up to the election. Even as the economy rates as the campaign’s top issue in all polling, which suggests Trump and Republicans have an edge, the attack ads have been less about inflation or the economy and more about transgender youth in sports or “tax dollars” that would “push an aggressive LGBTQ agenda on kids,” as one ad claims. Many of these have been false or misleading and have been called out as such in local media, but that hasn’t stopped the relentless pace of these ads.

So, how are these ads landing in this part of the state?

“I don’t think it resonates,” said Snodgrass. “I really don’t. I think it’s something that the MAGA base uses to instill fear and fire up their base. But I will tell you this, before people even know what party affiliation I am at the doors — I had a lot of ‘what are your top concern’ conversations this summer — there was not one person who said to me that transgender rights or girls playing in boys sports (was the top issue). I think they are overestimating that to their peril.”

“The anti-trans stuff I think is desperation,” said Lyerly. “I think that’s another thing that is just part of a culture war for people.”

“I think that’s a major turn off for most people,” said Welch. “Especially in our districts that are 50-50, essentially, and you’re talking about the need to get some independent (voters) over to your side, and I think if you’re an independent, that’s a huge turn off. That’s part of that culture war BS. It’s very unfriendly.”

“I think it’s going to fall flat,” said Spaude. “I think independent voters recognize that these anti-LGBTQ attacks, especially the attacks on trans kids, this is not a governing agenda. You cannot govern on this. If you’re an independent voter, what you want to know is what will this candidate do to help me out to keep more money in my pocket and these anti-LGBTQ attacks do nothing to help average voters.”

There’s a piece of this that many outsiders get wrong about a perceived level of social conservatism in places like the Fox Valley. This might be home to some people who hold those types of views on a personal level, but don’t always feel it should necessarily translate to public policy. Whereas where I grew up in Waukesha County, the type of evangelical perspective that might want their government to get more involved in opposition to LGBT rights or abortion or other social issues with religious underpinnings, many people in the Fox Valley tend have a more Tim Walz-ian “mind your own damn business”-type of mentality.

It’s also the case that many of the Democratic candidates running for office in this part of the state are themselves part of the LGBTQ community. That’s true of Spaude, Rivera-Wagner, Snodgrass, and Alfheim.

“Collectively as we talk with each other and we’re joking around, we have given ourselves the moniker, “The gals, the gays, and a few good men,”” said Lyerly, laughing. “It’s great. And we’re all supporting each other.”

Rivera-Wagner says that while he thinks he will probably be making history “by the identities I possess” if he wins in November, “I tell people it’s not what it feels like.”

“I didn’t run to make history,” he said. “It doesn’t feel like the story. I don’t want it to be. It feels very normal. Sometimes when I’m knocking on doors and (people will) ask how my husband is doing, or will have a bilingual conversation, but no one thinks of that as unique.”

Perhaps in the region it’s less about judgment, but maybe more of confusion.

Hintz said these ads might resonate “partially just because it’s a new issue to a lot of people. I think there’s a lack of understanding. Not everybody knows somebody who’s trans.”

“Is there some confusion and lack of understanding in the conversation? Yes,” said Alfheim, who is openly lesbian. “But the first thing I did was go ask people. Because I didn’t understand. And I think if people would be, what’s the secret, be curious, not judgmental? Try that for once. I literally scheduled a meeting with a gender studies professor to help me understand. Because I don’t understand everything. I don’t have to, but I can try, and get a little bit of empathy.”

Alfheim says that it’s been irritating to see how “an extremely small population…becomes 25% to 30% of the conversation out there.”

“It’s asinine,” she said. “I do believe that the bulk of this community is more socially liberal than they’ve ever been, which is why the conversation has now gone from gay to trans. Because they’re trying to find the edge that people haven’t found comfort with.”

She adds, “What’s affecting your kitchen table? That ain’t it. Let’s talk about what affects your kitchen table, because those should be the priorities.”

There’s a lot of joy, a lot of hope among Democrats in the Fox Valley and Green Bay. But within that hope, there sits a level of fear, of dread, of another four years of Donald Trump and what that could do to the region, the state, the country, the world.

Trump could win in Wisconsin. He’s also clearly prioritized this region, too, with multiple rallies in Green Bay in recent months, including an especially well-attended one just last week. No one should be surprised by a Trump victory here in 2024. This is not 2016.

The Fox Valley and Green Bay region is a microcosm of the state not because it’s uniformly shifting in one certain direction, but because it embodies such multitudes. It is the deepening red of the rural areas. It is the exceedingly blue spots, like downtown Appleton. It is the everything in between in the places that will determine what direction our state and nation goes for the next four years and beyond. The Democratic Party should recognize that this region is ripe for the picking, that there is a path through this region to make meaningful long term change that, with sustained action, could transform the politics of the entire state.

I myself am a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh. While I was born and raised in Wisconsin — in Waukesha County, in particular — I don’t feel as if I really understood the state until I was living in Oshkosh, or until I started dating my now-wife, who is from a big family in the Fox Valley. It’s a more complicated place than it seems, and understanding these blue and purple cities in the region, often a short drive from what can feel like the middle of nowhere, is critical to recognizing the true nature of the state. There’s so many more layers to it than just the suburb vs. city dichotomy that I grew up around in the Milwaukee metro area.

But part of it is simple, too. There are so many hard-working people in the Fox Valley. Hard work is a core value of the region, whether you’re a Republican or a Democrat or, more often than anything, have a set of political views that exist somewhere outside of the conventional two-party structure.

People in the Fox Valley and Green Bay work harder than their politicians do. They’re not wrong to expect better representation for their communities as people themselves keep their head down, do the work, and provide for their families and loved ones.

I set out on this four-day trip to the region thinking that I’d have a clear understanding of where the Fox Valley was shifting. I thought this would be the place that determines the presidency, and that by spending time there and talking to candidates and racing up and down I-41 between Green Bay and Oshkosh that I’d return home to Milwaukee confident in the knowledge of where this place would break, and if we were headed toward a Trump or Harris victory on Nov. 5.

I didn’t return with the answer. I still don’t feel confident in how things might break, one way or the other. Maybe that’s just the nature of where the Fox Valley and Green Bay is in 2024. Even with signs pointing in a certain direction, those trends might not arrive in time to flip the state this year for this race.

But what I do know is that there is the foundation of something special that’s forming in the region. From candidates like Kristin Lyerly or Emily Tseffos who face long odds, but who are going to outwork their opponents anyway, and build the infrastructure for long-term change. From potential breakthroughs in representation in the region from candidates like Kristin Alfheim or Amaad Rivera-Wagner. People like Duane Shukoski or Christy Welch, running for the first time, or like Lee Snodgrass, helping set the stage for a new era for Democrats in the region. The “gals, gays and a few good men” defying the stereotypes. The hope, the fear, the joy, the desperation, the nauseous optimism. It’s all there, sitting on a razor’s edge, as people get ready to determine the fate of the nation, whether they like it or not.

I think back to being in the passenger seat of Emily Tseffos’ minivan on that sunny afternoon. All week, I’d been asking people about campaigns and candidates in the region that stood out, and they were all talking about Emily Tseffos’ campaign.

“She has impossible odds, but Emily Tseffos is working,” said Snodgrass. “She’s running circles around all of us. This woman is absolutely going full out.”

Driving along those roads, looking for people who might be willing to talk, talking about connections in the region, asking her about why she’s running, where the region is headed, and what might happen on Election Day, with her explaining to me just how and why she’s in it for the long haul, beyond November, to put in the work all year round, to better represent this community, and maybe — one door at a time — transform the future of the state of Wisconsin. And in the end, it’s simple.

“People are so deserving of good representation,” she said. “Taking care of your neighbor is not a partisan issue. It’s just the right thing to do.”

The Recombobulation Area is a reader-supported publication, part of the Civic Media network. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Want More Local News?

Civic Media

Civic Media Inc.

The Civic Media App

Put us in your pocket.